AIO, GEO, AEO, LLMO, AI Search Optimization, AI Search Marketing, Retrieval Optimization, SEO. Nobody agrees on what we call it, which means nobody agrees on what it is, what it does, or whether it’s distinct from SEO.

What are we even doing here?

This week I sat in on a GEO webinar because a person I really respect was one of the guests, and since I’m trying to try new things this year, I decided to actually read the comments thread for the first time in my life. During the webinar, which I will not name, the entire comments section devolved into people arguing about what to call the new SEO: GEO, AEO, SEO, or something else. I had to leave halfway through because of a dentist appointment. Last week I had an emergency root canal, and during the procedure the dentist broke a tool off into my canal, where it got stuck. It’s been an extraordinarily painful week. So I left the webinar to see if he could extract it with what he described as “an instrument I fabricated to retrieve the metal in your canal.” He couldn’t get it out, and now I likely have to get the tooth extracted.

Another new thing I’m doing this year is talking more about what’s on my mind, and my intent is to do this respectfully. But first, let’s talk about why we’re all having the wrong argument entirely.

This is part one of a five part series. Subscribe to my Substack to not miss the rest of 'em.

The Two Arguments

Two arguments keep surfacing in every conversation about AI search.

The first says it’s called SEO, and not because indexation equals citation, but because SEO as a discipline already covers the ground: intent research, topic modeling, content structure, technical optimization, internal linking, anchor text strategy, YMYL considerations, authority signals, and all the rest of it. The argument is that whatever tactics get pages cited by AI systems are a subset of this existing framework, and that there’s no new discipline here, just new applications of the same thinking.

The second says this changes everything, that traditional ranking signals are irrelevant, the old playbook is dead, SEO is dead, and we need entirely new frameworks, new metrics, and new job titles.

Neither argument has actually provided much about what, concretely, is different, or whether that difference is big enough to deserve its own name.

Here’s where the first argument is right. If a website isn’t indexed, it doesn’t exist in most of these new AI systems: ChatGPT search pulls from Google and Bing’s index, AI Overviews and AI Mode pull from Google’s index, and Perplexity has its own index plus Bing and Google API access. This isn’t controversial, it’s just how the architectures work, and indexation is the entry ticket.

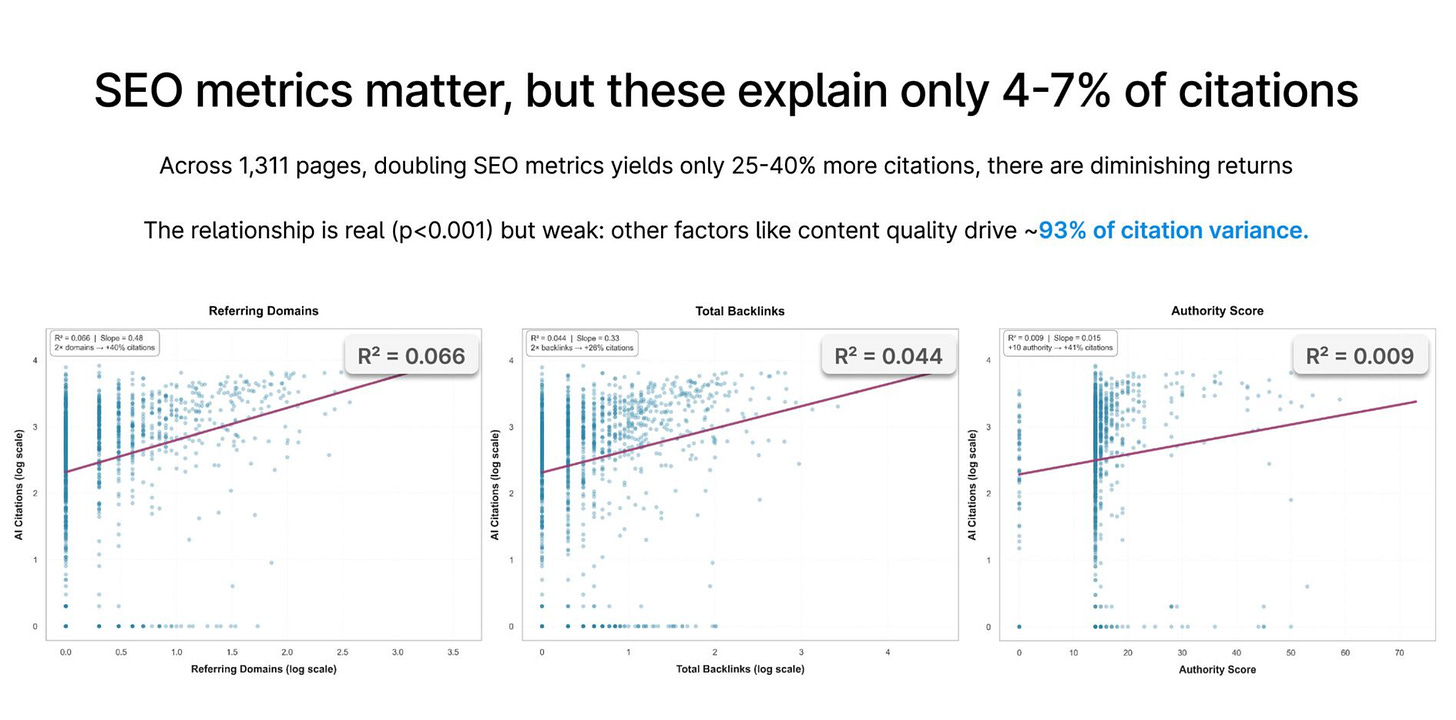

The “it’s different” crowd does have research to point to, and this example centers around backlinks. Backlinks have been a cornerstone of SEO since forever (my first SEO project was in 2006). It’s pretty common for practitioners to consider them a third of the entire discipline. The argument goes: once a website is indexed, backlinks barely move the needle for AI citations, which is saying that one of the largest pillars of traditional SEO is irrelevant.

Backlinks (AKA my least favorite SEO thing)

Profound’s team analyzed webpages to measure how backlink metrics correlate with AI citations:

<table style=”border-collapse:collapse;width:100%”><thead><tr><th style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;text-align:left”>Metric</th><th style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;text-align:left”>r² Value</th><th style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;text-align:left”>Translation</th></tr></thead><tbody><tr><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>Referring domains</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>0.066</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>Explains 6.6% of why pages get cited</td></tr><tr><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>Total backlinks</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>0.044</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>Explains 4.4%</td></tr><tr><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>Authority score</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>0.009</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>Explains 0.9%</td></tr><tr><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;font-weight:bold”>TOTAL</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;font-weight:bold”>0.119</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;font-weight:bold”>88.1% of why a passage is cited is not due to common SEO backlink metrics (referring domains, number of backlinks, and Authority Score).</td></tr></tbody></table>

Source: Profound/Josh Blyskal, Tech SEO Connect 2025 (Also BrightonSEO SD, I believe), based on 250 million AI search results

They say: Doubling backlinks would explain less than 5% more of whether pages get cited, so while the relationship exists, it’s not doing much. It’s worth noting: Profound sells a premium AEO tool to track prompts and advise on “AEO” tactics, so they have a business interest in this being a distinct and measurable discipline.

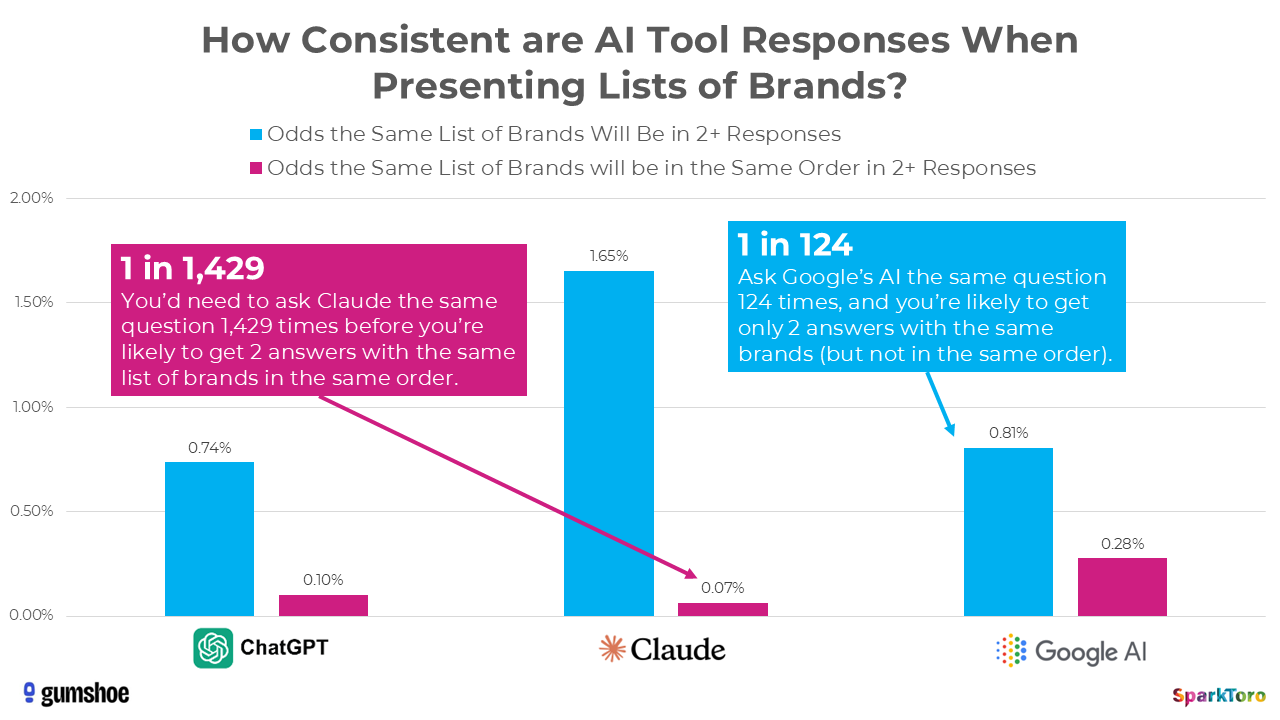

But then there’s yesterday’s research from SparkToro, which doesn’t uncomplicate things for us here: Rand Fishkin and Patrick O’Donnell ran an experiment asking whether AI tools are consistent enough to produce valid visibility metrics at all. They had 600 volunteers run 12 different prompts through ChatGPT, Claude, and Google’s AI tools nearly 3,000 times, and what they found was striking: there’s less than a 1 in 100 chance that any AI tool, if asked the same question 100 times, will give the same list of brands in any two responses. When it comes to ordering, it’s more like 1 in 1,000. The lists are so randomized that if you don’t like an answer, or your brand doesn’t show up where you want it to, you can just ask a few more times.

Their conclusion was that ranking position in AI responses is essentially meaningless to track, though visibility percentage across dozens or hundreds of prompts might be a reasonable metric. SparkToro sells audience research tools based on clickstream data, not AI optimization software, so their incentives point in a different direction than Profound’s. Though SparkToro did partner with Gumshoe, an AI tracking startup, for this research, which I say in an effort of transparency.

So we have one study saying backlinks don’t correlate with AI citations, and another study suggesting AI citations are so inconsistent that we’re not even sure what we’re measuring. This is not a foundation on which to build a new discipline.

The Profound research deserves scrutiny. They reference “SEO metrics,” and that phrase has been repeated everywhere out of context since. But what they actually measured was backlinks and authority scores. They didn’t touch technical SEO, they didn’t touch on-page optimization, and they didn’t measure content quality, topical authority, or freshness. However, they did actually take elements from those tactics and attribute them to AEO.

By the way: There are SEOs who have never reported a backlink metric in their lives and who get pages to rank through content depth and technical excellence (while allowing PR and brand authority substitute for SEO link building), and none of that showed up in this data. So when you hear “SEO only explains 4-7% of AI citations,” understand what that actually means: backlink metrics explain 4-7%, which is a very different claim than “SEO doesn’t matter.” I do think the study is valuable, but it measured one slice of SEO and LinkedIn crypto-turned-GEO bros ran with it, and to the industry’s detriment sold AEO/GEO to real companies, and now here we are.

Ranking is super muddy too

Two studies report seemingly contradictory numbers: Ahrefs found in August 2025 that only 12% of AI citations match Google’s top 10 for the same query, but an earlier Ahrefs study from July found that 76% of citations come from pages in the top 10 for some query. Both findings are true, and they’re measuring different things.

The explanation is query fan-out. When someone asks AI Mode a question, Deep Search fires hundreds of sub-queries, and each sub-query pulls from different top-10 results. A page in the number one position for “best running shoes” might get cited for a sub-query about “running shoe cushioning technology,” but not for the main response, which pulls from different sources for other sub-queries. So does ranking matter? It depends on what you mean by ranking, what you mean by matter, and which study you read last.

The point is: no matter what side you’re on, you can convince yourself that you’re right because there are so many studies with so many nuances, and the SEO industry is not one that I consider to have general awareness of what confirmation bias means and how it impacts the choices you make.

Both arguments have merit. The first is right that SEO fundamentals matter, that indexation is non-negotiable, that technical SEO still matters for crawlability and content structure, and that the discipline has always been broader than backlinks. The second is right that something is shifting, that the mechanics of how content gets surfaced and cited are changing in ways we don’t fully understand yet. But both arguments are skipping a step, which is the step where you actually define what you’re talking about before you fight about what to call it.

Before you can argue about whether GEO is distinct from SEO, you have to define what GEO actually is. Before you can claim the playbook is dead, you have to know which pages of it still work. And before you name a discipline, you have to know what practitioners of that discipline are supposed to do. Right now, nobody can answer those questions concretely. We have studies showing backlinks don’t correlate with AI citations, and studies showing AI citations are too inconsistent to measure reliably. We have contradictory data on whether ranking matters. We have vendors selling optimization for a system whose behavior they can’t predict. We have Google telling us there is nothing special you need to do; it’s just SEO. And conversely we have Bing calling it AEO/GEO, complete with a 16-page guide!

The question isn’t what we call this thing. The question is whether “this thing” exists as a coherent practice at all, or whether we’re drawing a circle around a bunch of disconnected tactics and calling it a discipline because that’s easier to sell.

So here’s what I’m going to do with the rest of this piece. I’m going to try to define what’s actually different about optimizing for AI systems, which means skipping past the vibes and acronyms and vendor pitches and focusing on the mechanics: what happens after indexation, what determines whether a page gets cited, and whether any of it constitutes a practice distinct enough from SEO to deserve its own name. Maybe it does. Maybe the SEOs had it right all along. But we’re not going to know until we do the work that everyone skipped while they were busy arguing about what to call it.

Did I mention my tooth is screaming?

Problem 1: The terms all mean the same thing to the people using them, but I think they’re all wrong.

AIO, which stands for AI Optimization, is the vaguest of the bunch. It could mean optimizing for training, inference, retrieval, or literally anything involving AI systems.

GEO, Generative Engine Optimization, comes from a Princeton and Georgia Tech research paper published in November 2023. It’s specifically about how content appears in generative AI outputs, and the original research found that simple methods like keyword stuffing, which are traditionally used in SEO, often perform worse in generative engines. So already we have a term whose source material suggests the old tactics don’t work, but which has been adopted by people who mostly just do the old tactics with new names.

AEO, Answer Engine Optimization, actually predates modern AI search. It originally referred to featured snippets and voice search optimization, and some practitioners have repurposed it for AI, which means it now refers to two different things depending on who’s using it. I don’t know anyone serious who was calling voice search optimization AEO before this, but here we are.

LLMO, Large Language Model Optimization, is technically accurate but confusingly broad. It could mean optimizing for AI training data, chatbot responses, or search results, and those are all different problems with different solutions.

AI Search Optimization is descriptive, but it treats “AI search” like it’s one thing, which it isn’t. It’s at least five different systems with different architectures, which brings us to the next problem.

Retrieval Optimization is what I’ve been using (🤗Tyler, you’re so smart and unique /s), because it describes the actual mechanism: AI systems retrieve content before generating responses, so you’re optimizing for the retrieval layer. But even this doesn’t account for the differences between systems and architectures, and I’m not convinced it’s the right frame either.

None of these terms are perfect, and in this piece I’ll use them interchangeably because to most people they all refer to the same vague idea. Just know that the terminology itself is part of the confusion, and the fact that we have at least six different names for something we can’t define should tell you something about where we are as an industry.

Problem 2: There is no unified “AI search” to optimize for

There are at least five major systems, and they all have different architectures.

Google AI Overviews pulls from Google’s index via FastSearch.

Google AI Mode, a separate system powered by Gemini 3, adds Google’s Knowledge Graph, Shopping Graph and a suite of AI tools to a chat-like interface. Note: I will come back to this after I dig into the new search experience that Google announced on January 26th.

ChatGPT Search depends on Bing and sometimes Google and does real-time page fetching.

Perplexity has its own index of what they claim is “hundreds of billions of URLs” while also using Bing and Google (according to Reddit) APIs.

Microsoft Copilot runs through Bing via Prometheus orchestration, and they’re in the process of modernizing it by enabling specialized autonomous agents that are capable of managing complex, multi-step tasks across user workflows as well as NLweb.

This doesn’t even account for personal agents, which we will see at scale this year. A great example of this is Clawdbot (now called Moltbot), which took off on Twitter last week, and drove a ton of Mac Mini sales, security issues, a Cloudflare stock price increase, and Anthropic bans for misuse of Max plans. What I learned with my isolated Clawdbot setup was that the Brave Search and Brave Data for AI APIs were incredible additions to my personal agent. I found a car battery to fit my car that was in stock nearby in 30 seconds. All I had to do was add to cart and go through the PayPal purchase process. The reason I bring this up is: how do you optimize for that experience? What do you call it? Is it the same discipline as getting your blog to show up in a ChatGPT deep research session? It’s not. And I’m not sure you can deliberately optimize for a single, personalized experience like that at all. Not to mention UCP/ACP protocols from Google and OpenAI, which I will save for a different time.

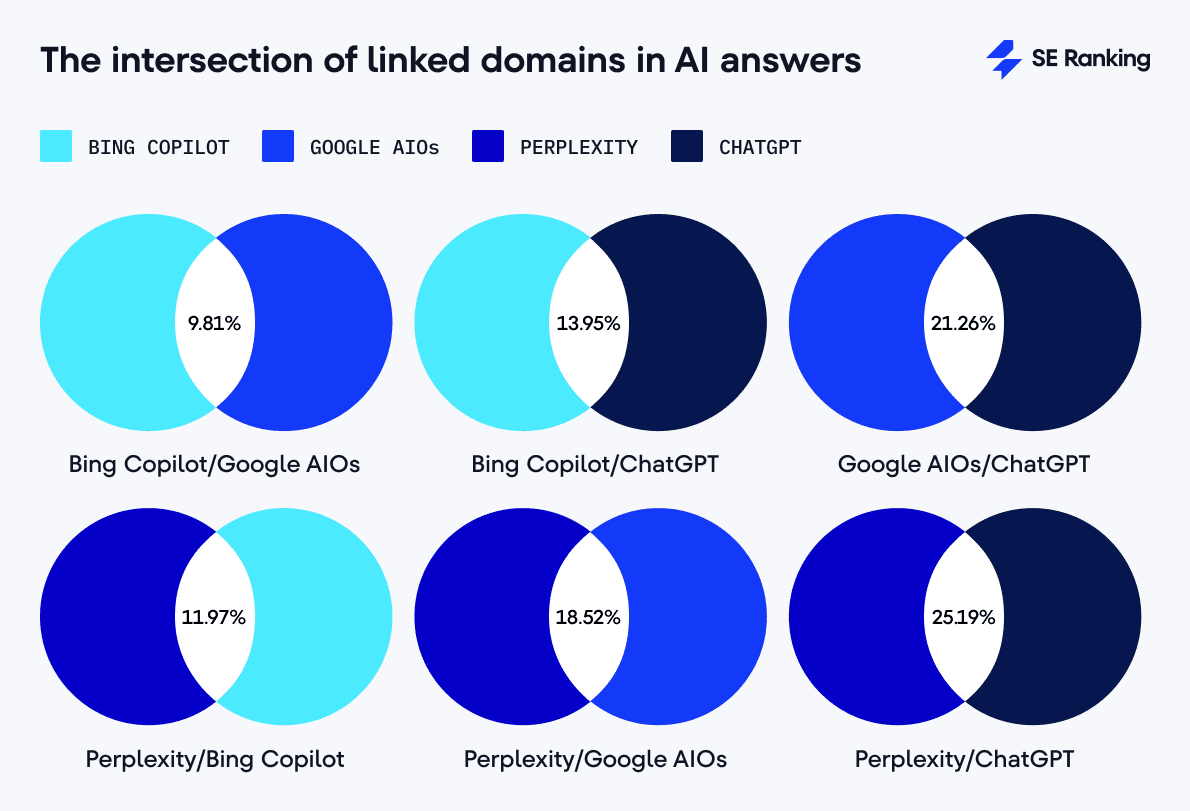

The citation overlap between platforms ranges from 6% to 21% and helps us understand an angle of this:

<table style=”border-collapse:collapse;width:100%”><thead><tr><th style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;text-align:left”>Platforms</th><th style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;text-align:left”>Citation Overlap</th><th style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px;text-align:left”>Source</th></tr></thead><tbody><tr><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>ChatGPT ↔ AI Overviews</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>21.26%</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”><a href=”https://seranking.com/blog/chatgpt-vs-perplexity-vs-google-vs-bing-comparison-research/”>SE Ranking</a></td></tr><tr><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>ChatGPT ↔ Perplexity</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>11%</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”><a href=”https://www.tryprofound.com/blog/citation-overlap-strategy”>Profound</a></td></tr><tr><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>Perplexity ↔ AI Overviews</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>16.4% or 18.5%</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”><a href=”https://www.tryprofound.com/blog/citation-overlap-strategy”>Profound</a> / <a href=”https://seranking.com/blog/chatgpt-vs-perplexity-vs-google-vs-bing-comparison-research/”>SE Ranking</a></td></tr><tr><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>AI Overviews ↔ Copilot</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”>6% or 9.81%</td><td style=”border:1px solid #888;padding:12px”><a href=”https://www.tryprofound.com/blog/citation-overlap-strategy”>Profound</a> / <a href=”https://seranking.com/blog/chatgpt-vs-perplexity-vs-google-vs-bing-comparison-research/”>SE Ranking</a></td></tr></tbody></table>

Each system is pulling from entirely different sources for the same queries, which means optimizing for one platform might do nothing for another. But the SparkToro research from yesterday suggests the problem goes deeper than cross-platform fragmentation. Even within a single platform, asking the same question 100 times produces a different list of recommendations almost every time. The inconsistency isn’t just between ChatGPT and Perplexity, it’s between ChatGPT and ChatGPT. So we’re not only dealing with five different systems that behave differently from each other, we’re dealing with five different systems that can’t even behave consistently with themselves.

So when someone tells you they do GEO, or AEO, or AI Search Optimization, the first question should be: for which system? And the second question should be: how are you measuring success when the system gives different answers every time you ask? If they don’t have answers to both, they’re selling you a discipline that doesn’t exist yet.

So here’s what I’m going to do with the rest of this series.

- In part two, I’m going to get into the actual architectures: how Google AI Overviews, Google AI Mode, ChatGPT, Perplexity, Copilot, and Claude work under the hood, what they’re pulling from, and why that matters for anyone trying to show up in them. This is going to be gnarly.

- In part three, I’m going to lay out every piece of research I could find that seems noteworthy, including where the studies contradict each other and why.

- In part four, I’m going to fact-check the claims that keep circulating, because I’m noticing most of them are wrong or outdated or missing context that changes everything.

- In part five then I’ll get case studies, how to it’s being measured, and what to do when you’re staring at a strategy doc wondering where to even start. Fair warning here - there is not much out there. And usually if there is it’s a product of confirmation bias.

And then, once we’ve done all that work, maybe you all can agree on a new name for SEO.

.png)